Soviet awards to Norwegian patriots

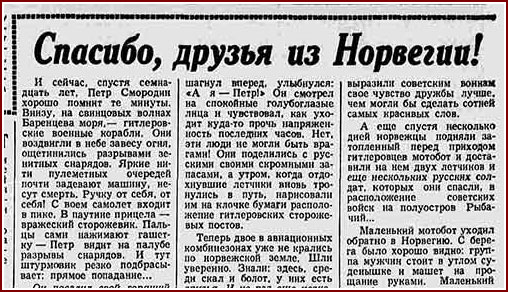

Germany occupied Norway on 9 April 1940 and controlled this Scandinavian country until the surrender of German troops in Europe on 8 May 1945. Many citizens participated in the Resistance Movement, in strikes and sabotage and in partisan struggle. Today our story is about Norwegian patriots who were awarded Soviet orders and medals for courage and bravery in rescuing Soviet soldiers and helping them during World War II.

During the war, there were around one hundred thousand Soviet prisoners of war on Norwegian territory. Despite threats from the German administration (prison or even death penalty), many Norwegians helped them. The most famous of them was "Russian mother" Marie Østrem, who together with her husband Rheingold helped prisoners of war by collecting food, clothing, money and shelter for Soviet soldiers who escaped from the camp.

By decree on 11 November 1958, Marie Østrem and Rheingold Østrem were awarded the Order of the Patriotic War (first degree) and the Medal for Victory over Germany for the courage shown in the rescue of prisoners of war.

The awards were personally presented to them in Moscow by Kliment Voroshilov.

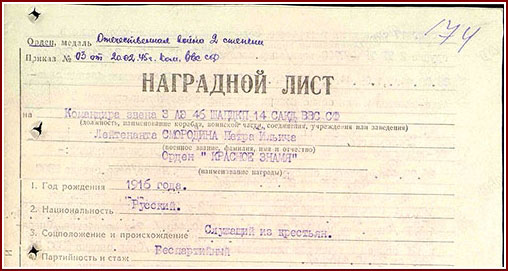

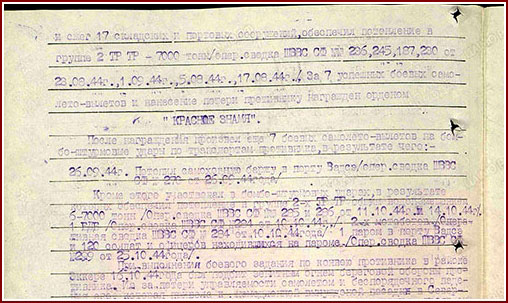

On 16 October 1944, in Varanger Fjord, the German convoy was attacked by Northern Fleet pilots. The operation was attended by an IL-2 attack aircraft, with a crew consisting of a pilot, lieutenant Pyotr Ilyich Smorodin and radio operator-gunner Yuri Ivanovich Potekhin.

The German anti-aircraft gun hit the plane in the tail section and the aircraft was disabled. The pilots managed to land the plane at Cape Svartnes. Having established their location, they decided to try to pass along Varanger Fjord and get to the Soviet troops. They took weapons, emergency food supply and a map of the area where their operation was taking place. The pilots preferred to go around at night, when the possibility of their detection was the least. On the third day around 10 p.m., they came across a dugout. Human voices were heard inside, but the pilots could not make out whether they spoke Norwegian or German. Holding their pistols ready, they entered the dugout, where they saw two men and two women in civilian clothes. The dugout, which was in the pasture near the Storelvdalen Valley, belonged to 61-year-old Olga Vikki, who moved here due to air raids on the city.

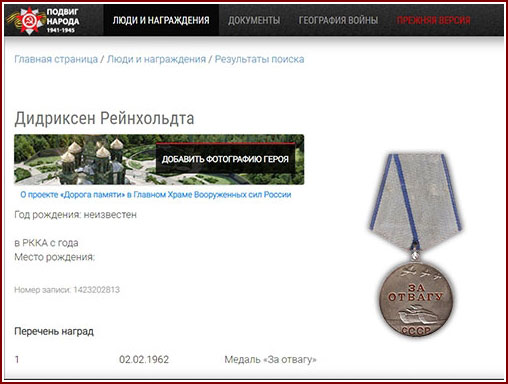

In her youth, Frau Vikki came across Pomor merchants and learned to speak Russian. Little by little, she found a common language with Soviet pilots. Her daughter Olga Didriksen lived here with her husband Reinholdt Didriksen and her second son-in-law Johan Berswensen.

The Russians introduced themselves and explained the situation. They showed on the map the place where their plane was left and explained that they wanted to go to Vadsø and try to find a boat to cross the fjord. When the residents of the dugout explained to them that the city and the highway were teeming with Germans, the pilots had to abandon the plan.

The Vikki family noticed that the two strangers were very tired and decided to leave them for the night, although there was not much room in the dugout, which only covers 7-8 m2. The Russians gratefully accepted the offer and, after dinner, the hosts and guests went to bed. That night, Frau Vikki did not sleep a wink. The Russians slept soundly on the floor with their guns beside them, but Frau Vikki was afraid that one of the neighbors might have noticed two strangers in uniform entering and raising an alarm, or that a German patrol would appear in the area and it would come to a shootout. But when dawn came, everything was still calm. After sharing a modest breakfast with the hospitable Norwegians, the Russians pulled out a map and explained that they wanted to go around the Varanger Fjord and get to Soviet troops as originally planned. After being shown the most convenient way, they said goodbye to friendly family and headed west. On their way they met locals and everywhere received food and a place to sleep.

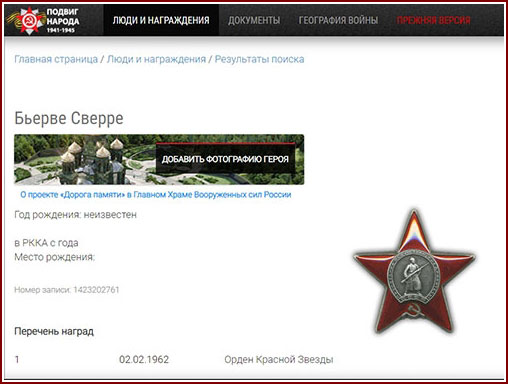

When police officer Sverre Bjørve was ordered by the Germans to vacate the premises, he arranged a meeting where all the employees came. At the meeting, he announced that it was up to everyone to decide whether they wanted to evacuate or stay. Sverre went home and changed into civilian clothes, put warm clothes, a woollen blanket, a sleeping bag and a supply of food in his backpack, and in the evening, after dark, he went to the mountains, where he gathered on a wood shed, where he decided to spend the night. In the morning he realised where he was and decided to stay here, as he felt that this place was far enough away from the main roads.

One afternoon, while he was sleeping, the door opened and a guy in a leather jacket, a flight helmet, with a bag on his back and a gun appeared on the doorstep. He looked at the police officer and said him a few words that Sverre did not understand at all. Sverre knew German well and since he did not understand a word of what the stranger had said to him, he decided that the stranger was Russian. The three men began to explain themselves through gestures, signs and a few Russian words that Sverre knew. After a long discussion, he found out about their plan to reach the Soviet troops and managed to make them understand that in the current situation, when German units are moving along the roads day and night, this plan is completely unrealistic. Eventually, the two of them stayed in the barn with him.

One day a man, dressed in civilian clothes, approached the barn. Behind his shoulder he had an automatic rifle, but before he could take aim, when he ran into the barn, the Russians ran out of the door with their weapons. Fortunately, the shootout did not get to the point. When a stranger saw the pilots' uniform, he spoke to them in Russian, and it turned out that he himself was a Russian scout, A. Mikhailenko, who had parachuted off a few days ago. Soon they were able to be ferried by fishing boat to the Rybachy Peninsula.

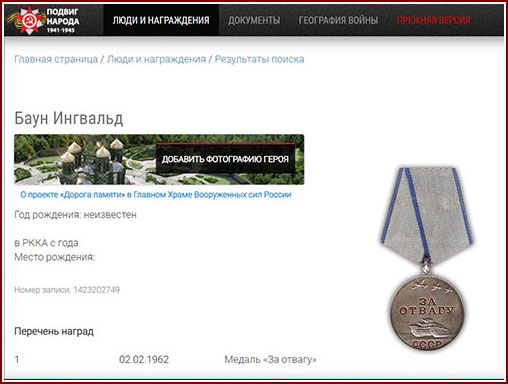

In autumn 1944, there many Russian pilots, escaped prisoners and scouts on the Varanger Peninsula. Some of them took refuge in the mountains. This was the case, for example, with two Russians who were taken to Cape Skallelv. It is not known whether they were pilots from a plane crash or scouts. They were ferried from Skallelv to the Rybachy Peninsula. The fishing boat on which they were sailing belonged to Kristian Kvalvik, who was the skipper on that voyage.

The bot team consisted of Ingvald and Helmer Baun, Birger Basso, Håkon Eriksen, Eugene Terentyev and Ragnvald Ananiassen.

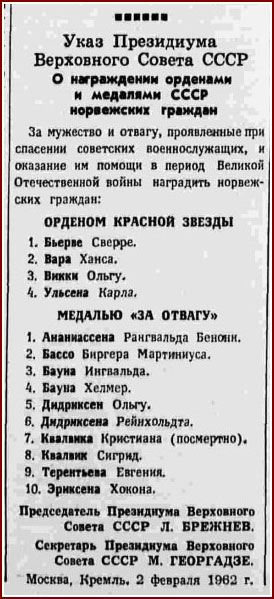

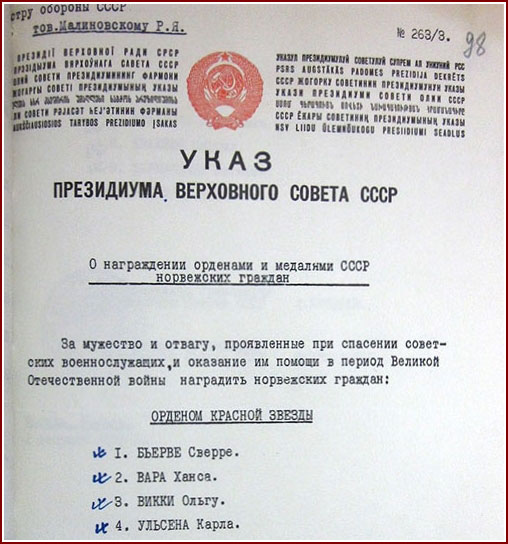

By decree on 2 February 1962, 14 Norwegian citizens were awarded orders and medals for their courage and bravery in rescuing Soviet soldiers.

For this operation, Lieutenant Smorodin was awarded the Order of Patriotic War (second degree).

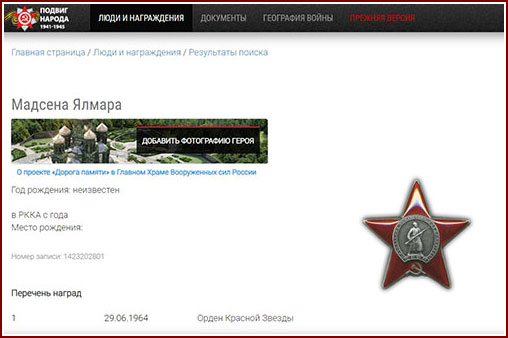

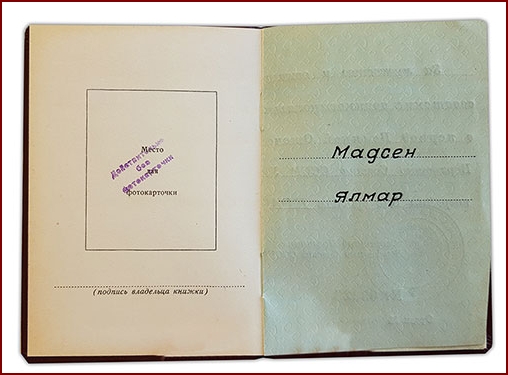

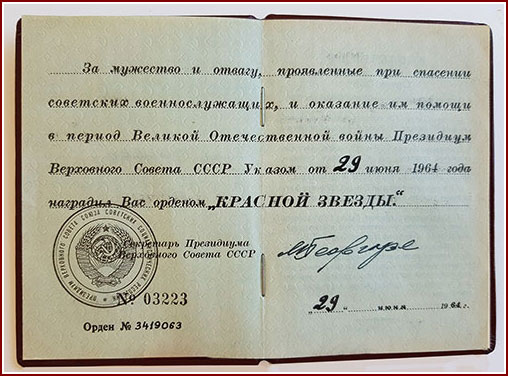

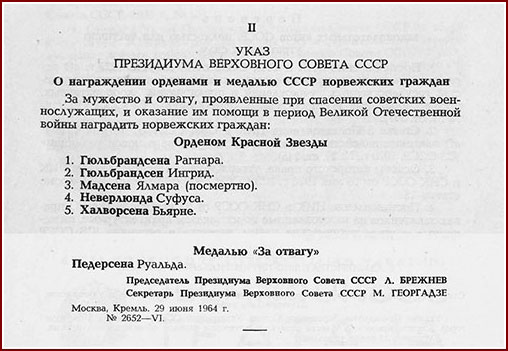

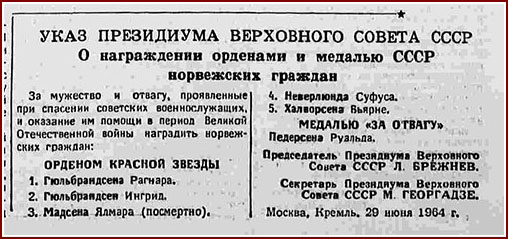

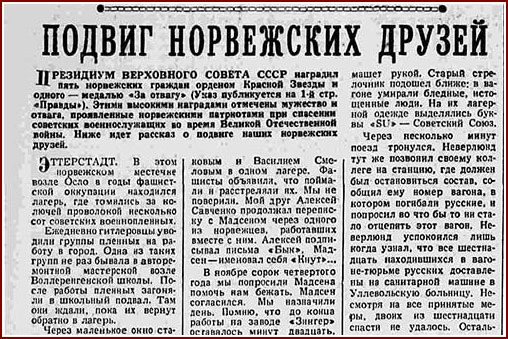

Etterstad. In this area of Oslo during the years of occupation, there was a camp where several hundred Soviet prisoners of war were kept. German soldiers took groups of prisoners to work in the city every day. One such group worked in a car repair shop near the Vollerenga School. After work, the prisoners were taken to the school cellar. There they waited until they were brought back to the camp. The Norwegian patriots, led by journalist Hjalmar Madsen, who knew Russian, began handing them bread and tobacco through a small window.

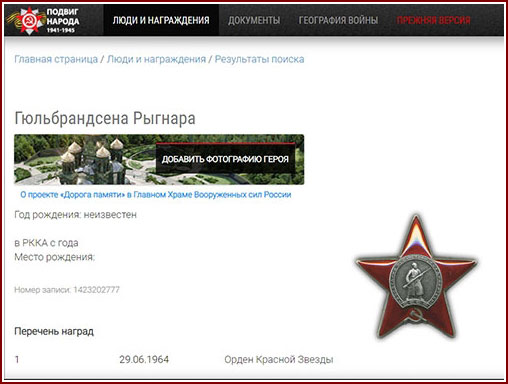

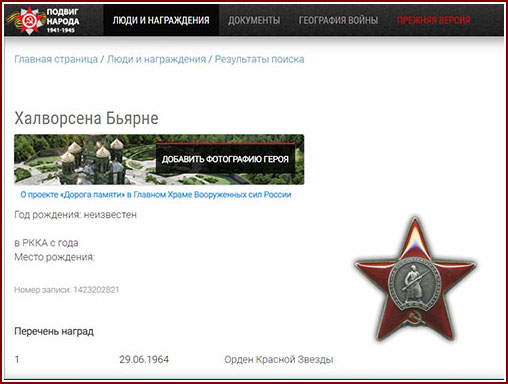

One day, in the late autumn of 1943, Hjalmar Madsen, painter Ragnar Gulbransen and construction worker Bjarne Halvorsen approached the school. Two from the cellar climbed the stack of firewood, climbed over barbed wire and ran away with the Norwegians. So Fyodor Bychkov and Vasily Smelov escaped from captivity. The escaped prisoners lived in a small flat on the Gothenburg Gate for about a month and later they were transported to Sweden.

In the spring of 1944, Arkady Smiyan and Nikolai Yermolov decided to escape from the camp. In broad daylight, in front of German soldiers, two Soviet prisoners of war, dressed in civilian clothes given to them by the Norwegians, left the factory gate to the street, got on bicycles prepared by them and went to home on Lillebergsvingen, where Bjarne Halvorsen lived with his wife. In November 1944, Hjalmar Madsen and his comrades helped Vladimir Arkhipov, Alexei Savchenko and Peter Teslitsky to escape.

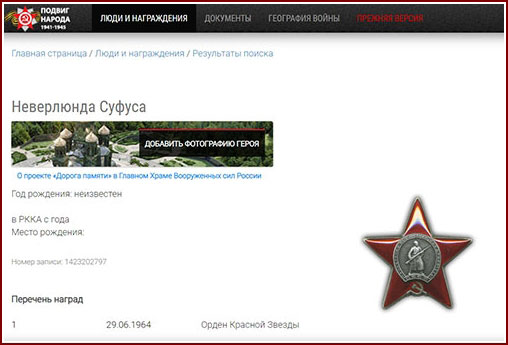

On 10 May 1945, a long train stopped in Oslo, near the Eastern Station. Switchman Sufus Neverlund used to tap the wheels with a hammer. Suddenly he saw someone waving from the boxcar. Pale, exhausted people were dying in the wagon. The letters "SU" - Soviet Union - stood out on their camp clothing. A few minutes later, the train moved. Neverelund immediately called his colleague at the station where the train was supposed to stop, gave him the number of the wagon and asked him to unhook this wagon. Sixteen people were taken to Ullevål Hospital. Two of them could not be saved. The others had recovered, and Sufus Neverlund often visited them at the hospital.

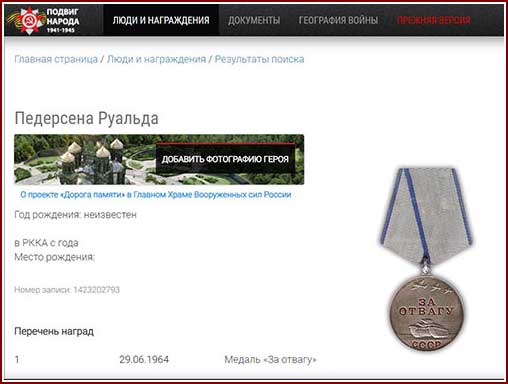

Roald Pedersen was only thirteen years old at the end of the war. One day he learned from a German that the camp authorities had received an order to kill the prisoners by injecting poison under the guise of vaccination. Roald lived near the camp, and many times he secretly handed over food to the prisoners. Now he warned the Russians to beware of vaccinations. And when paramedics with medical syringes appeared near the barracks, the prisoners rebelled and refused the vaccinations, thus saving their lives.

By Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR of 29 June 1964, six Norwegian citizens were awarded orders and medals for their courage and bravery in rescuing Soviet soldiers.

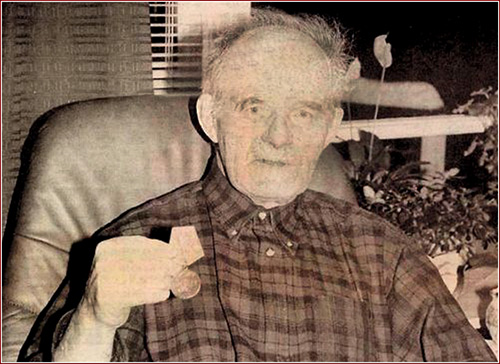

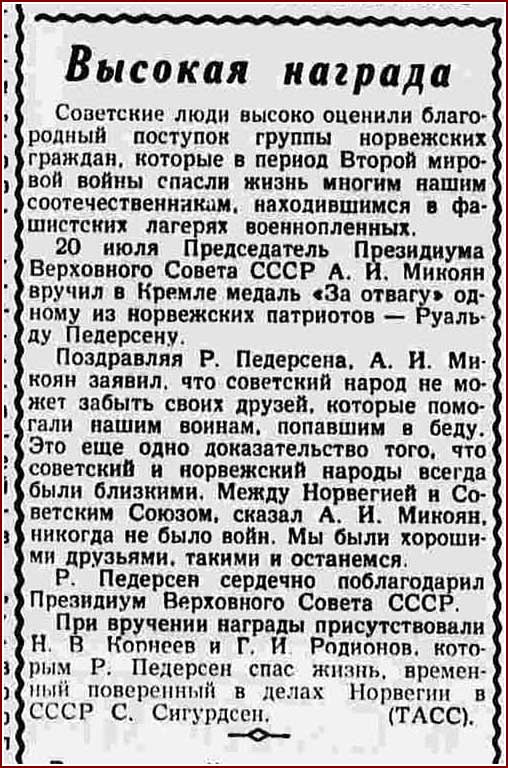

On 20 July 1964, Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR A. Mikoyan presented the Medal For Courage to Roald Pedersen in the Kremlin. The award ceremony was attended by N. V. Korneev and G. I. Rodionov, whom Ruald Pedersen saved life.

On 20 October 1944, escorting a group of IL-2 planes in the Arctic, two squadrons of the 19th Guards Fighter Regiment, led by Captains P.Z. Kochegin and G.F. Dmitryuk, met eleven Yu-87 bombers and twelve Me-109 fighters behind the front line. Dmitryuk's group attacked the bombers. The eight, led by Kochegin, continued to accompany the attack aircraft. At the very target, the group was attacked by six M-109. Repulsing their attacks, S.N. Slyunin set fire to a fascist plane. The attackers, having completed the task, headed for their own aerodrome. Captain Kochegin ordered a pair of Slyunin to accompany the attackers, and self with Junior Lieutenant R.M.Sereda imposed a fight on the Messerschmitt, trying to pull them aside.

In one of the frontal attacks, Kochegin was shot down by a German fighter plane. But soon he was shot down too, so he had to jump with a parachute. The landing took place near Lake Salmijärvi, in the territory occupied by the enemy. He managed to get away from the chase and hide in the swamp. At night, on reaching the highway, Captain Kochegin met a Norwegian peasant Bjorn Beddari.

Bjorn took the Soviet pilot to his friend Sigvart Larsen's farm.

Soon Harald Knudtsen, a Russian-speaking engineer, appeared in Larsen's little room.

The Norwegians fed the pilot and provided him with medical care. Harald assured the pilot: "Don't worry, Pavel, you are among real friends". Soon the advancing Soviet troops came here.

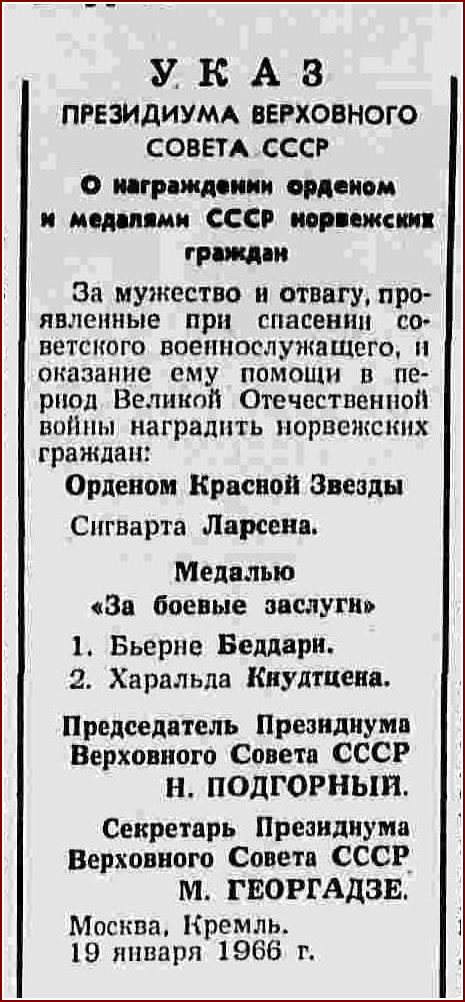

By the Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR of 19 January 1966, Sigvart Larsen was awarded the Order of the Red Star, and Bjorn Beddari and Harald Knudtsen were awarded the Medal for Combat Services.

Pavel Kochegin wrote the book "Dawn in the sky of the polar lands", which he dedicated to his Norwegian friends.

Unfortunately, not all Norwegian patriots were awarded for their achievements.

For example, when, after the Germans were expelled, access to Soviet POW camps became free, residents of towns and cities visited the camps daily with flowers, food parcels and clothing. To this end, initiative groups from the local population were set up in the camps' districts, which included representatives of medical institutions. Doctor Arne Helme from Oslo visited one of the camps. He selected nine almost hopeless patients and brought them to his home for treatment. Dr Helme's efforts were a complete success.

A few years later, in celebration of the decade of liberation in the northern province of Finnmark, Air Marshal F. J. Falalayev, who headed the Soviet delegation, visited Dr Arne Helme and expressed his gratitude for his noble deed. Dr Helme was extremely touched by the Marshal's visit.

In his memoirs, F. Falalayev wrote: I went to this doctor - thanked him on behalf of the Soviet government. Upon my arrival in Moscow, I presented him to the government award through the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the General Personnel Department of the Soviet Army. But apparently his request was not granted.

This is the first material on Norwegian patriots who was awarded with Soviet awards. In the following chapters we will talk about partisans who helped Soviet troops in the north.

Sources:

- Marie Østrem

- Pavel Kochegin

- Щербаков В. И. Заполярье - судьба моя.

- Фалалеев Ф. Я. В строю крылатых.

- Кочегин П. З. В небе полярных зорь.

- Харальд Риесто "Маленький город и война: Вадсё в 1941-1945 гг."

- Marie Østrem, Marie Østrems dagbok.